Cyrano

Last month, Peter Dinklage was a guest on Marc Maron's podcast, and shared his thoughts on the upcoming Disney live-action remake of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs": “You’re progressive in one way, but you’re still making that [expletive] backward story about seven dwarfs living in a cave together. Have I done nothing to advance the cause from my soapbox? I guess I’m not loud enough.” Twitter reacted badly, as Twitter is wont to do. People were lecturing him about how dwarfs were common in Germany mythology (you can't make this stuff up), people were telling him it's a "fairytale," "it's not that deep," stop overthinking it, calm down. I thought his criticisms were perfectly valid. His comments highlighted the unique nature of his career. "Groundbreaking" doesn't even cover it. He won four Emmys for his performance as Tyrion Lannister in "Game of Thrones," but that's just the beginning in terms of accolades. Dinklage "advances the cause" even further in his performance as Cyrano de Bergerac in "Cyrano," the new musical adaptation of Edmond Rostand’s 19th-century play, directed by Joe Wright, and it feels a little bit like casting as destiny. It makes so much sense! In Rostand's play, Cyrano (based loosely on a real person) has many gifts. He is a soldier. He is brave. But there's one problem. He has a gigantic nose, and has internalized the world's opinion that he is ugly. He loves the beautiful Roxanne but knows he can never have her. In this adaptation, written by Erica Schmidt (Dinklage's wife), it is Cyrano's stature that holds him back from love and intimacy, not his nose, and the transfer really works, giving the melodramatic well-known story an undeniable base of reality. Normally, actors wear prosthetic noses when they play the role. The audience knows it's not a real nose, and everyone buys the convention. Remove the convention, though, remove that layer of artifice, and all kinds of other things are possible. As Cyrano, Dinklage is impulsive and bold, openly emotional, and fearlessly dramatic in his gestures and his voice. The language is poetic and heightened, and he shows great skill in filling it, expressing it. Cyrano and Roxanne (a radiant Haley Bennett) are childhood friends, and their closeness and intimacy breaks the lovelorn Cyrano's heart all the more. Roxanne confides in him. She is being "courted" by a slimy Duke (Ben Mendelsohn, sporting a cape and a beauty spot), but she has fallen in love-at-first-sight with a young recruit in Cyrano's regiment, the handsome Christian (Kelvin Harrison Jr.). Christian loves Roxanne too but is tongue-tied in her presence. He begs Cyrano to write love letters to Roxanne on his behalf. Cyrano agrees, and Roxanne is swept away by Christian's passionate and poetic eloquence. We all know this situation cannot go on forever. Most audiences are familiar with the bare bones of the story, since the play is such a favorite in repertory companies, as well as the many film adaptations. The most well-known version is probably Steve Martin's "Roxanne," a whimsical riff on the original (with all the stark tragedy removed). José Ferrer's performance in the 1950 film is well worth seeking out, as is Gerard Depardieu's 1990 version. Everyone brings something different to the role. What's so much fun about Dinklage's performance is how it's in many ways a throwback. At one point, he single-handedly defeats ten men with his dazzling swordsmanship. The men come at him from every side, dropping down on him from above, and he flips and jumps and slashes, dispatching them all. It's a thrilling sequence, calling to mind Douglas Fairbanks, Errol Flynn, and all the great movie swashbucklers of days gone by. And yet at the same time, there's something wholly modern about what he brings. This is an extremely personal performance, and he is at times truly heartbreaking. It should be noted that this adaptation started off as a 2019 off-Broadway production, starring Dinklage (and directed by Schmidt). The score was composed by twin brothers Aaron Dessner and Bryce Dessner (of the band The National), with lyrics by National frontman Matt Berninger and Carin Besser. The songs aren't stereotypically "catchy," either in a Broadway way, or a pop-anthem way. They're mostly used as interior soliloquies expressing the intense emotions of unrequited love, passion, desolation. Joe Wright's handling of these numbers—in collaboration with cinematographer Seamus McGarvey—is very interesting. There is choreography, in a sense, but it's woven into the fabric of the scene: there's a beautiful moment where rows and rows of soldiers fence one another in rhythmic coordination, lunging and thrusting out onto the parapets above the sea; or bakers kneading dough in time with the music, the dances erupting out from everyday activities. It's very eye-catching and intricate, fun to watch. There are lags at times, and Christian's fumbling and bumbling could have been given much more screen time, for the

Last month, Peter Dinklage was a guest on Marc Maron's podcast, and shared his thoughts on the upcoming Disney live-action remake of "Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs": “You’re progressive in one way, but you’re still making that [expletive] backward story about seven dwarfs living in a cave together. Have I done nothing to advance the cause from my soapbox? I guess I’m not loud enough.” Twitter reacted badly, as Twitter is wont to do. People were lecturing him about how dwarfs were common in Germany mythology (you can't make this stuff up), people were telling him it's a "fairytale," "it's not that deep," stop overthinking it, calm down.

I thought his criticisms were perfectly valid. His comments highlighted the unique nature of his career. "Groundbreaking" doesn't even cover it. He won four Emmys for his performance as Tyrion Lannister in "Game of Thrones," but that's just the beginning in terms of accolades. Dinklage "advances the cause" even further in his performance as Cyrano de Bergerac in "Cyrano," the new musical adaptation of Edmond Rostand’s 19th-century play, directed by Joe Wright, and it feels a little bit like casting as destiny. It makes so much sense!

In Rostand's play, Cyrano (based loosely on a real person) has many gifts. He is a soldier. He is brave. But there's one problem. He has a gigantic nose, and has internalized the world's opinion that he is ugly. He loves the beautiful Roxanne but knows he can never have her. In this adaptation, written by Erica Schmidt (Dinklage's wife), it is Cyrano's stature that holds him back from love and intimacy, not his nose, and the transfer really works, giving the melodramatic well-known story an undeniable base of reality. Normally, actors wear prosthetic noses when they play the role. The audience knows it's not a real nose, and everyone buys the convention. Remove the convention, though, remove that layer of artifice, and all kinds of other things are possible.

As Cyrano, Dinklage is impulsive and bold, openly emotional, and fearlessly dramatic in his gestures and his voice. The language is poetic and heightened, and he shows great skill in filling it, expressing it. Cyrano and Roxanne (a radiant Haley Bennett) are childhood friends, and their closeness and intimacy breaks the lovelorn Cyrano's heart all the more. Roxanne confides in him. She is being "courted" by a slimy Duke (Ben Mendelsohn, sporting a cape and a beauty spot), but she has fallen in love-at-first-sight with a young recruit in Cyrano's regiment, the handsome Christian (Kelvin Harrison Jr.). Christian loves Roxanne too but is tongue-tied in her presence. He begs Cyrano to write love letters to Roxanne on his behalf. Cyrano agrees, and Roxanne is swept away by Christian's passionate and poetic eloquence. We all know this situation cannot go on forever.

Most audiences are familiar with the bare bones of the story, since the play is such a favorite in repertory companies, as well as the many film adaptations. The most well-known version is probably Steve Martin's "Roxanne," a whimsical riff on the original (with all the stark tragedy removed). José Ferrer's performance in the 1950 film is well worth seeking out, as is Gerard Depardieu's 1990 version. Everyone brings something different to the role. What's so much fun about Dinklage's performance is how it's in many ways a throwback. At one point, he single-handedly defeats ten men with his dazzling swordsmanship. The men come at him from every side, dropping down on him from above, and he flips and jumps and slashes, dispatching them all. It's a thrilling sequence, calling to mind Douglas Fairbanks, Errol Flynn, and all the great movie swashbucklers of days gone by. And yet at the same time, there's something wholly modern about what he brings. This is an extremely personal performance, and he is at times truly heartbreaking.

It should be noted that this adaptation started off as a 2019 off-Broadway production, starring Dinklage (and directed by Schmidt). The score was composed by twin brothers Aaron Dessner and Bryce Dessner (of the band The National), with lyrics by National frontman Matt Berninger and Carin Besser. The songs aren't stereotypically "catchy," either in a Broadway way, or a pop-anthem way. They're mostly used as interior soliloquies expressing the intense emotions of unrequited love, passion, desolation.

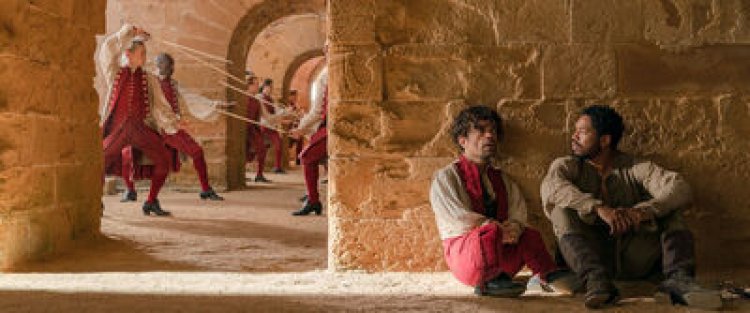

Joe Wright's handling of these numbers—in collaboration with cinematographer Seamus McGarvey—is very interesting. There is choreography, in a sense, but it's woven into the fabric of the scene: there's a beautiful moment where rows and rows of soldiers fence one another in rhythmic coordination, lunging and thrusting out onto the parapets above the sea; or bakers kneading dough in time with the music, the dances erupting out from everyday activities. It's very eye-catching and intricate, fun to watch. There are lags at times, and Christian's fumbling and bumbling could have been given much more screen time, for the comedic element alone. It's not driven home just how much Christian cannot talk to save his life.

The montage sequence of the letter-writing is the real standout. It's a passionate three-way dance of longing, the letters flying back and forth, Cyrano lost in composing the letters, Roxane lost in reading them. The letters flutter through the air—in her room, around her bed, falling down onto her body, drifting down onto the streets—a rapt metaphor of what it feels like to read a love letter. The person's voice is in your head. It's transportive. It's erotic.

The tragedy in Cyrano comes from people who choose half-truths over the full truth, who refuse to risk emotional exposure. These lies create loneliness. This is the human condition, particularly when love comes into play. What if when he gets to know me, he doesn't like me? What if she sees the real me and doesn't like what she sees? People wear masks. People pose. And in so doing they practically guarantee their continued isolation.

This is the heart of Cyrano de Bergerac. This is why the play has been in constant rotation ever since it premiered in 1897. It's not just a farcical story about a guy with a big nose who gets roped into writing love letters to the woman he can't have. It's an ethical and moral tale, with a strong warning against letting fear of rejection, or fear of being humiliated, stop you from speaking your truth, from living in truth. Cyrano is fearless in a duel, but when facing the woman he loves, he quakes. "Cyrano" gets the big things right, and Dinklage embodies it all.

Now playing in theaters.

:quality(85):upscale()/2025/02/27/808/n/1922398/26784cf967c0adcd4c0950.54527747_.jpg)