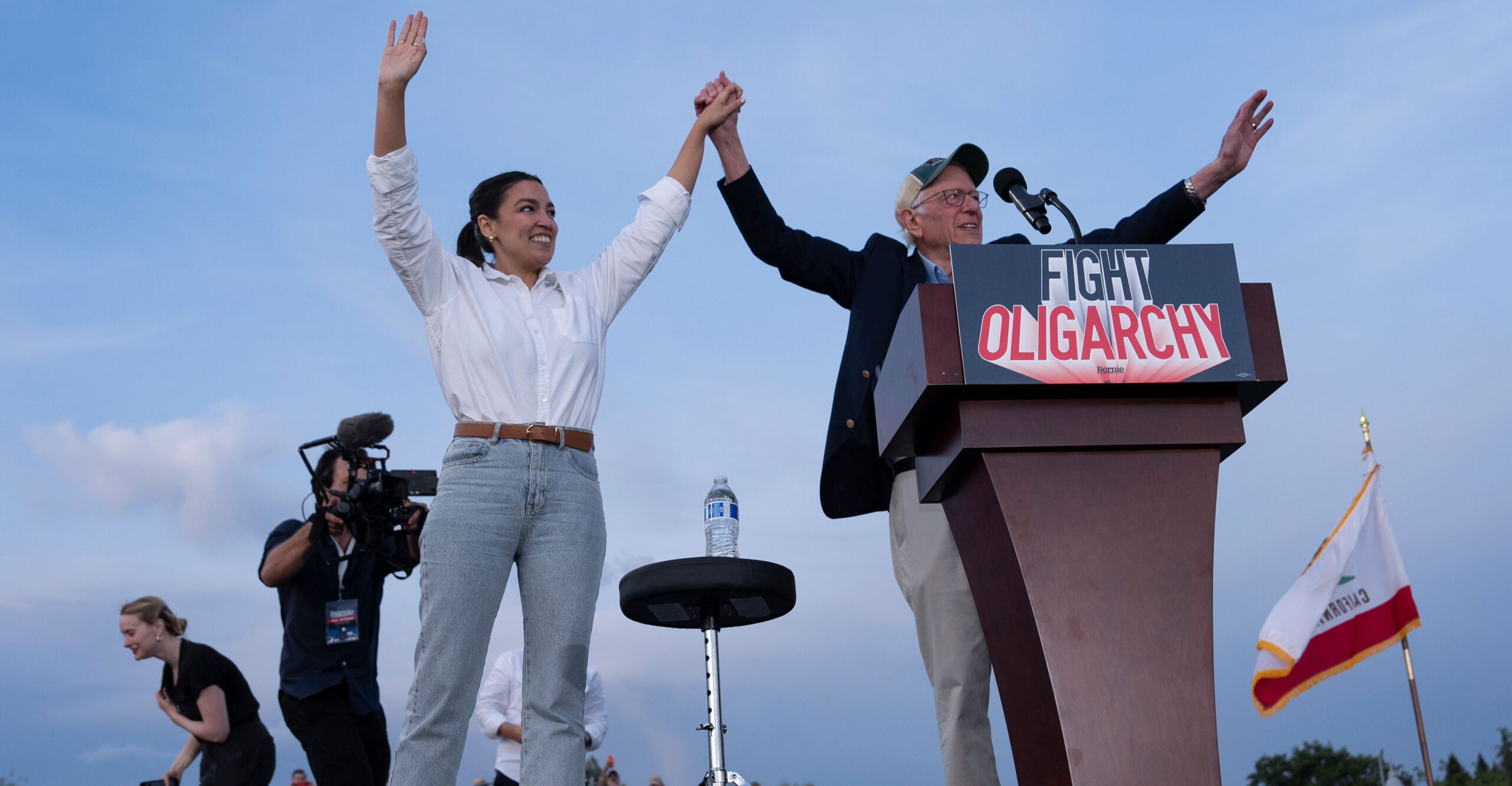

Environmental permit you never heard of could clean, or foul, local waters

Officials will set tougher pollution rules for storm drains three counties. But how tough, and how expensive, remain open questions.

At least 10,000 people were expected to hit local beaches and rivers and streams for Coastal Cleanup Day on Saturday, Sept. 21, picking up trash and generally sprucing up places – the coastline and inland waterways – that help make Southern California what it is.

But eight days earlier, on a Friday, Sept. 13, exactly zero members of the general public came to the Cypress Civic Center for an open meeting about how Region 8 of the California Water Board should write its next MS4 permit.

The document that was under discussion will set limits and other rules about any pollution that spills out of storm drains and flood control channels in much of Orange, Riverside and San Bernardino counties over the rest of this decade. (Los Angeles County goes through the same process.) And some of its proposed details – including a first-time effort to create a watershed management plan that might lead to tighter rules against wayward dischargers – are controversial.

Public works officials from several cities and counties testified in Cypress, many talking about how expensive the new MS4 might become for their taxpayers. So did business people and consultants, some of whom figure to spend or make money based on whatever rules eventually wind up in the new permit. The room also included one clean-water advocate, Garry Brown, founder of Orange County Coastkeeper, who later described the current draft of the region’s next MS4 as “a big, tragic step backward.”

Overall, as events go, the differences between beach beautification and permit-a-palooza were like a battle between ice cream and broccoli.

“It wasn’t exciting,” Brown said.

Which isn’t the same as unimportant.

Environmental experts of all stripes say Coastal Cleanup Day is a vivid reminder to political and business interests that the people who vote for them, pay their salaries and buy their products really like their beaches and water to be clean.

But those same experts also say MS4 permitting – which centers around an almost comical level of scientific and legal detail – is the bigger deal.

If the Clean Water Act of 1972 offered an idealistic view of water-related environmental goals, legislating rules that could lead to drinkable fresh water in urban settings and oceans devoid of dirt, the MS4 permits issued to cities, counties and other agencies around the country are less poetic, reflecting the actual lengths to which each community will and won’t go to reach environmental goals.

The Clean Water Act initially took aim at so-called “single source” polluters, such as businesses and water treatment plants. The MS4 permit system (the label is short for Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems) reflects the simple fact that lots of people living near water will, by living and working, create lots of water pollution.

If a restaurant worker washes garbage cans and a bunch of microbes get into a storm drain, that can be regulated by an MS4 permit. Ditto if a guy tosses the used oil from his Prius into the gutter, or a university allows untreated wastewater to flow into its storm drains, or a farmer doesn’t limit the pesticides and fertilizers that flow off her crops into a viaduct.

As of last year, the Environmental Protection Agency estimated there were about 7,250 MS4 permits issued in the United States to cities, counties and thousands of other entities that are legally responsible for tracking and – when possible – limiting the stuff that flows off their properties.

“The MS4 is sort of where reality happens,” Brown said.

Or, as Monte Alvarez, a retired lawyer in Ontario who learned about MS4 permits when he represented home builders in Texas in the mid-1990s, put it:

“They’re boring. But they matter.”

And the MS4 being negotiated in Region 8, which is made up of 60 cities, counties and other governmental districts surrounding the Santa Ana River watershed, could matter a lot to anybody who pays taxes, goes to the beach or, like most people in Southern California, does both.

“It’s an important document,” said Amanda Carr, deputy director of the environmental resources division for Orange County Public Works and the county’s lead negotiator in the new MS4 permit, which by law is supposed to be in effect for five years.

“And it will be in effect for several years.”

Cities, suburbs, farms

To understand why the region’s new MS4 is important – and why it’s so hard to craft – you’ve got to understand a little about the region and the evolving ways humans tend to pollute.

The California Water Board breaks down the state by bodies of water, not political boundaries. And though federal and state laws have to be followed, MS4 permits issued in each region also reflect the environmental, economic and political challenges that are specific to their area.

For example, the stretch of Los Angeles County defined by the California Water Board as Region 4, centered around the Los Angeles River, is one of world’s biggest cities. About seven million people and businesses in Region 4 send all manner of stuff into aging sewers and storm drains that eventually flow into the river basin and, later, the ocean.

That sheer volume – not a sudden, community-wide disinterest in the environment – is why big rainstorms last fall and winter overtaxed Region 4 storm drains to the point that they flowed into the Los Angeles County sewer system, sending an estimated 38 million gallons of raw waste into city streets and the Pacific Ocean.

But threats to the water in Region 4 differ from the threats posed in the more agricultural Region 7, which includes parts of Imperial, Riverside and San Diego counties, and is centered around the watershed connected to that area’s stretch of the Colorado River. Region 7, in turn, differs from Region 9, which includes the stretch of Orange County south of El Toro Road and much of coastal San Diego County and is centered on San Diego Bay and the San Diego River watershed.

In the context of how the Water Board defines its districts, Region 8 is somewhat unusual.

Like the other regions, it’s built around a watershed – the Santa Ana River. But that watershed touches urban, suburban and agricultural communities in near equal parts. Carr, who has worked in Orange County for most of her career and led divisions of Public Works since 2016, explained that stormwater pollutants within Region 8 can differ dramatically, depending on what kind of community you’re talking about.

For example, farms generate more fertilizer-related harmful nutrients (a phrase akin to “jumbo shrimp,” but, in this case, it means deleterious levels of stuff that might be acceptable or even beneficial at a lower level). Suburbs spew more bacteria (typically from human and pet waste and decaying plants), and cities churn out things like tire rubber and metals used in various manufacturing processes.

But the proposed MS4 will apply to all of Region 8, meaning its rules will have to address a vast range of pollution issues.

“The permittees are held to all water quality standards equally, so we are charged with complying with all water quality standards for any pollutants that are found in stormwater that are above the approved standards,” Carr wrote via email.

Closed sessions?

The next MS4, under discussion since last year, is likely to take effect next year, according to Carr and others. Most of the draft meetings, so far, have included representatives from the counties and cities that will have to enforce the rules and punish any violators.

Those discussions have used scientific data produced by the Southern California Coastal Water Research Project, a public research institute in Costa Mesa that studies water quality in the ocean and throughout the region and supplies information for agencies creating MS4s and other permits.

Coastkeeper’s Brown suggests a key constituent has been left out of the process – water.

“The draft of the permit, from our perspective, is worse than what we have,” Brown said.

He claimed nobody from his organization, or any other nonprofit advocating specifically for water quality, was part of the discussion prior to the meeting in Cypress earlier this month.

“They’ve had 22 meetings, so far, and they’ve had consultants for at least some of them. But we haven’t been invited, nor has anybody else advocating for water quality.”

Brown, who helped negotiate the existing MS4, said he understands the pressure that will be in play as a final draft of the new permit is hammered out, probably over the next six months.

“When cities and counties look at this they’re looking at dollar signs,” Brown said. “The stiffer the permit, the more enforceability, means more dollars they don’t have a budget to cover.

“But I also think they want to do the right thing, too,” he added.

“We’re trying to raise the bar, and I don’t necessarily think that’s going to be opposed.”

Carr, who said she is interested in public works because she’s interested in improving the environment, and that she’s confident everyone on her 70-person staff feels the same way, said environmental concerns will be key to any final draft for the next MS4.

“That’s the point of all this.”

:quality(85):upscale()/2024/12/02/919/n/1922398/2b4b75f6674e20edcc99c3.42112799_.jpg)