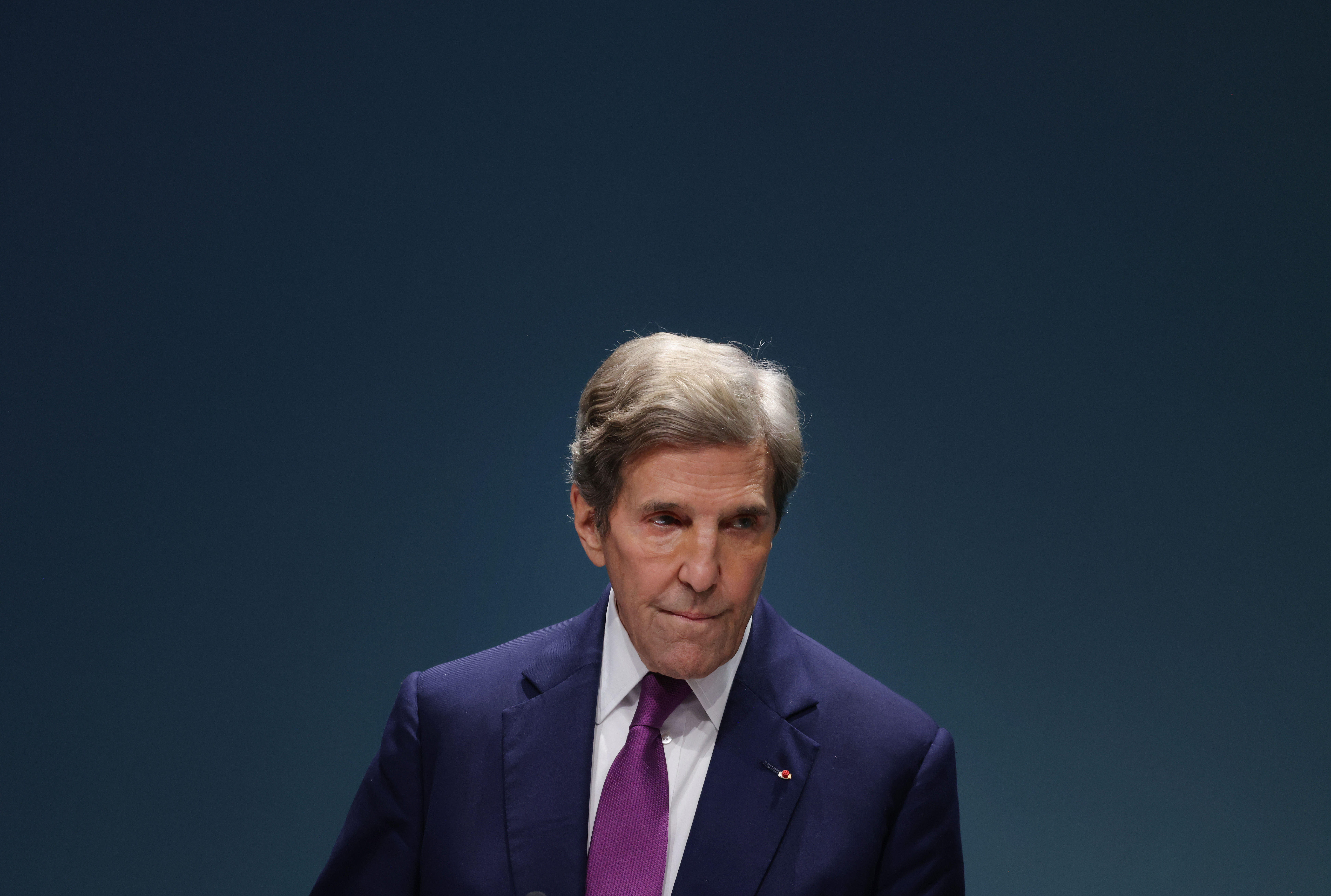

John Kerry to step down as Biden climate envoy

The veteran diplomat helped craft the 2015 Paris climate agreement, and more recently led the U.S. team at COP28 in Dubai.

John Kerry plans to step down from his position as President Joe Biden’s special climate envoy in late winter or early spring, a person familiar with his plans told POLITICO on Saturday.

The person was granted anonymity to discuss a move that has not been publicly announced.

Kerry’s departure from the position comes just weeks after he led the U.S. negotiating team at the U.N. climate conference in Dubai, where countries for the first time agreed to work toward transitioning away from using fossil fuels in the coming decades. Carbon pollution from those fuels helped drive the world’s temperatures to the highest level in recorded history last year.

The news was first reported by Axios, which said Kerry plans to help Biden’s reelection campaign. Mitch Landrieu, Biden’s infrastructure czar, also recently announced he would leave his position to join the campaign effort. Kerry is leaving at a crucial juncture for U.S. climate diplomacy — but also at a time when the most dire threat to Biden’s climate goals is a potential second term for former President Donald Trump.

Kerry, 80, has been a fixture in the United States’ climate diplomacy for decades — and before that, as a senator who unsuccessfully sponsored a major climate bill during the early Obama administration, pushing it with such fervor that one fellow Democrat told POLITICO in 2010 that it’s “all climate, all the time with him.”

Five years later, as Obama’s secretary of State, he helped negotiate the Paris climate agreement, which established the framework in which countries agreed to set their own domestic targets for reducing greenhouse gas pollution. The agreement set a goal of keeping temperatures from climbing no more than 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, as well as a more ambitious stretch target of 1.5 degrees.

He built a strong rapport with China’s lead climate negotiator, Xie Zhenhua, who is leaving his post as well. The relationship between the two veteran diplomats often yielded agreements between world’s top two greenhouse gas emitters to combat the pollution, even as they struggled to maintain momentum for tackling climate issues amid the rising tensions between Washington and Beijing.

“John Kerry was an historic diplomat not only for our country, but for the entire planet,” Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) — who occupies Kerry’s former seat in the Senate — wrote Saturday on X.

Kerry played a key role in reasserting U.S. climate leadership on the global stage after four years of Trump, giving the U.S. a respected hand committed to the international climate architecture that in many ways he helped shape.

“He was instrumental in reestablishing U.S. credibility on climate and helping drive other countries to step-up their efforts. His imprint is all over the increased action we have seen the last couple of years,” Jake Schmidt, senior strategic director of international climate with the Natural Resources Defense Council said via text.

“It definitely marks the end of an era,” said David Waskow, director of international climate at the World Resources Institute.

He said he remembers observing Kerry meet with representatives of island nations at the 2007 U.N. climate summit in Bali, Indonesia, when Kerry was still a senator for Massachusetts. “He clearly cared about their plight and understood what needed to happen to fight climate change.”

Next year, nations are expected to agree on a new target for delivering climate finance to developing countries to help cope with the effects of climate change and install more clean energy — a notoriously tricky issue that the U.S. often faces criticism for since it hasn’t delivered on past pledges.

Rich countries failed to meet a goal they set in 2009 to amass $100 billion in annual climate finance by 2020, a figure that experts say is modest compared to the trillions of dollars that will be needed to keep temperatures rises in check.

“The administration will have to place significant attention on those negotiations,” said Waskow. “It can’t let Kerry’s departure let that slide off the radar.”

Kerry has supported various options for generating more of the needed aid for less developed countries, for example by leveraging money from corporations and international institutions such as the World Bank.

At the same time, he has led the U.S. opposition to proposals from some developing countries that the United States feared would make it legally liable for the irreversible losses imposed by its many decades of climate pollution. Instead, the U.S. agreed in 2022 to the creation of a climate “loss and damage” fund to help poorer nations, while insisting that all contributions from wealthy governments would be voluntary.

Last year in Dubai, the U.S. pledged $17.5 million to the fund, falling well behind much smaller countries like Italy, Germany and the United Arab Emirates. And it is not clear the U.S. can even follow through on that promise given stiff Republican opposition.

Kerry had previously deflected pressure from activists for the U.S. government to drop large sums of money into the fund, stating at a 2022 forum that he lives in the “zone of reality.”

For all the wrangling over money, Kerry expressed optimism that the world can cut its greenhouse gas pollution fast enough to stave off catastrophe.

“I’m more interested in how are we are going to get rid of these emissions and win the battle — which we can win,” Kerry said at the same forum.

Nate Hultman, a former senior adviser to Kerry, credited the envoy not only with navigating the complex negotiations at last month’s COP28 climate talks but with the work he’s done to cut the oil and gas industry’s emissions of methane, a greenhouse gas with far more warming potential than carbon dioxide.

“I think it’s a tremendous legacy he’s leaving,” said Hultman, who’s now director of the Center for Global Sustainability at the University of Maryland.